Book Reviews- Art - General

A "crocodile shark" sea monster from a novel by by Takizawa Bakin

This beautiful volume was published by the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, in conjunction with their “Showdown! Kuniyoshi vs. Kunisada” exhibition in 2017, which I had the great pleasure of seeing. The idea was to pit these two late Edo era print geniuses “against” each other. Exhibition attendees were then asked to consider which designer they liked better (a question I found impossible to answer).

Having seen the exhibition I can say that this companion book is worthy of that majestic event, during which some of the finest prints of the quarter-millennium Edo era were on display. Not only were these prints superb in terms of their artistry and subject matter, they also were in a state of preservation you’re not likely to find in too many places around the world (museums, galleries, private collections).

But that’s typical of the MFA’s Japanese print collections, which were donated largely by wealthy collectors early last century, who either knew what they were doing or had agents - such as Frank Lloyd Wright - scout top quality purchase opportunities. (Wright was a Japanophile, collector, and dealer in Japanese prints. His architectural work including interior design was heavily influenced by Japanese art and architecture. Wright’s “Taliesin West” is a great example, and well worth visiting - or at least having a look online.)

Many prints in this exhibition almost shock with their striking, deeply saturated colors. I’m happy to report that the photography in this book does a great job capturing that effect.

Who were Kuniyoshi and Kunisada? Each belonged to the Utagawa School, which was the predominant school of 19th century Japanese print designers - and which included superstar Ando (Utagawa) Hiroshige in its ranks. Utagawa school designers worked in a variety of genres, with Kunisada best known for his actor prints and Kuniyoshi for his historical warrior prints, and for “monsters” such as giant fish of Japanese legend.

While today we think of Hokusai and Hiroshige as the standout 19th century Japanese print designers, in fact during that century the two biggest names were Kuniyoshi and Kunisada. The book’s Preface points out that Kunisada created some 20,000 to 35,000 designs, while Kuniyoshi produced designs in the 10,000 range. Estimates for Hiroshige range from 4500 to 10,000 - with the broad range due to uncertainty about attribution. As for Hokusai, the author points out that he largely turned away from prints and toward painting after completing his great landscape series in the 1830s.

Many Kuniyoshi and Kunisada print designs were too in-your-face for early Japanese print critics, who often described their work as “decadent”. Certainly the book includes striking examples of how K & K subjects went well beyond their illustrious predecessors’ typical output. Battle scenes full of energy, grim faced actors, supernatural creatures attacking mere mortals - all were too much for the critics.

So for most of the 20th century the two designers took a decided back seat to Hokusai and Hiroshige - and to a large extent that view holds to this day. But recent decades have seen a revival of interest in their work, with the 2017 MFA exhibition perhaps constituting a watershed moment for K & K. At the very least they are exceptional artists, with a command of color, line, and form. Like them or not, their work is unforgettable.

For those who really want to dig in, the book includes essays by six experts, and an appendix with commentary on each print selected for inclusion here from the exhibition.

While not a comprehensive study, this book is a good introduction to Utamaro’s work and what is known about his life. Utamaro did not limit himself to courtesan prints, and in fact was a superb painter as well as print designer - though most of the plates in this book are devoted to that subject. This can hardly be a criticism however, because Utamaro is to 18th century courtesan prints what Picasso is to cubism. It’s unusual to think of either of them in another context.

Author Tadashi Kobayashi’s background is presented on the dust jacket. It indicates a life devoted to studying and writing about Japanese art, along with serving as a curator at the Tokyo National Museum. So it’s no surprise that he writes with authority and insight. The book includes solid material on the ukiyo (“floating world”) milieu which engendered Japanese prints during the Edo period.

While there are other, comprehensive books about Utamaro, for the most part they are scholarly tomes which may not appeal to those looking for a good introduction to Utamaro’s life and art. On that basis you won’t go far wrong with this book.

The remainder of our review provides context for the main focus of Utamaro’s work - courtesans of the Yoshiwara - and is in our “Articles" section under this title: Utamaro, the Yoshiwara, and the Courtesan - a Brief Introduction

Well-researched, well-organized, thorough introduction to Japanese prints. Excellent chapter on how prints are created. Many illustrations, beautifully photographed. Highly recommended.

If you’re willing to splurge a little, or are looking for a beautiful gift for an art lover, this one is my recommendation. Based on a 2015 Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition of the same title, this book dazzles with its screen and scroll paintings of the Kano School, which dates to the late 15th Century. A huge plus is the explanatory text which accompanies each section of the book. Kano paintings are known for their expansive landscapes and beautifully rendered trees and animals. The great Kano artists had no lack of commissions providing art for the high and mighty, and for wealthy merchants. If you didn’t know otherwise you could easily assume this art is Chinese, and for good reason. Kano, like much of Japanese culture, was heavily influenced by China. As I look through the photographed screens and scrolls, I realize that adjectives like “stunning” and “breathtaking” are simply inadequate. If you get this book you’ll know exactly what I mean.

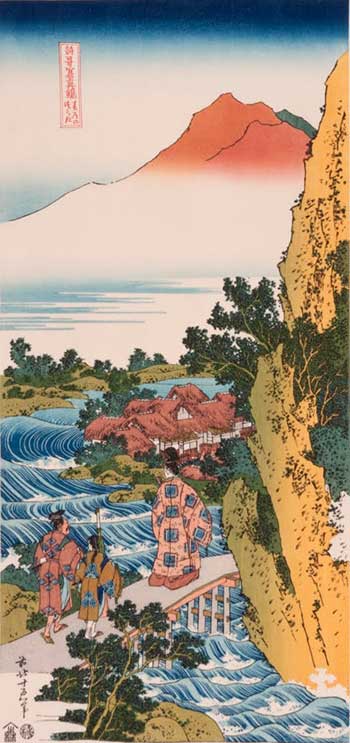

James Michener, of course, is known to the world for his geographical-historical novels. He picked regions like Hawaii or Israel or Iberia, thoroughly researched their histories and topographies, and produced epic novels which became giant best sellers. What’s far less known about Michener is that he also was an art connoisseur, and nourished a lifelong fascination with Asia. Here, Michener combines both attributes to produce a volume about Japanese prints which is written with the same painstaking research and novelistic flair which characterize his best sellers, and—to add interest for current readers—from the post-war perspective of the 1950s. It quickly became a classic in the world of Japanese prints.

This work is a comprehensive introduction (really more than an introduction) to Ukiyo-e, which translates to Pictures of the Floating World. “Pictures” here refers to prints, primarily prints of the Edo era (17th through mid-19th Centuries). The term “floating world” came to characterize the hedonistic merchant culture of the Tokugawa shogunate—a wonderfully ironic twist on its original Buddhist meaning, which counseled rising above transitory material desire to achieve nirvana. Michener writes in a conversational manner and delivers a big dose of foundational material for understanding Edo era print subject matter. Included is a chapter on the classical Japanese print-making process, which is the finest description of that subject I’ve read—and which reaffirms Michener’s prodigious literary talent.

So rich is this text that it can be read on different levels. You can read for information on prints, artists and the Edo era generally. You can read for Michener’s engaging take on all this. And if you’re looking to start an education in Japanese prints as art, you can study Michener taking apart one print after another—in terms of line, color, spatial relationships, and anything else which makes a print successful or not.

I mentioned that this book was written in the 1950s—published in 1954 to be exact. At the time, it was the only general interest work on the subject published in decades (in English, at least), according to commentary by Howard A. Link which is included as an appendix to the 1983 edition. Since original publication in the 1950s academic specialization in East Asia studies had grown exponentially, making this book something of a target for fact-checking PhDs. You’ll find their comments in the appendix by Mr. Link. My take is that this appendix is intended more for scholars than for the general interest reader—for whom Link’s conclusions are more important:

It is entirely possible that many in the English-speaking world would never have become interested in these “little scraps of paper” (i.e., Japanese prints) if it had not been for James A. Michener... it took a man such as Michener, with the ability to accurately summarize complex issues, to popularize the subject for the average person... and is all the more to his credit that he did so with such affection and enthusiasm for the print and the Japanese artists who produced them.

More than thirty years later—and over sixty years since release of the first edition—these conclusions still look good.